Urgent Solutions Needed to Protect Pregnant Women from the Severe Effects of Climate Change

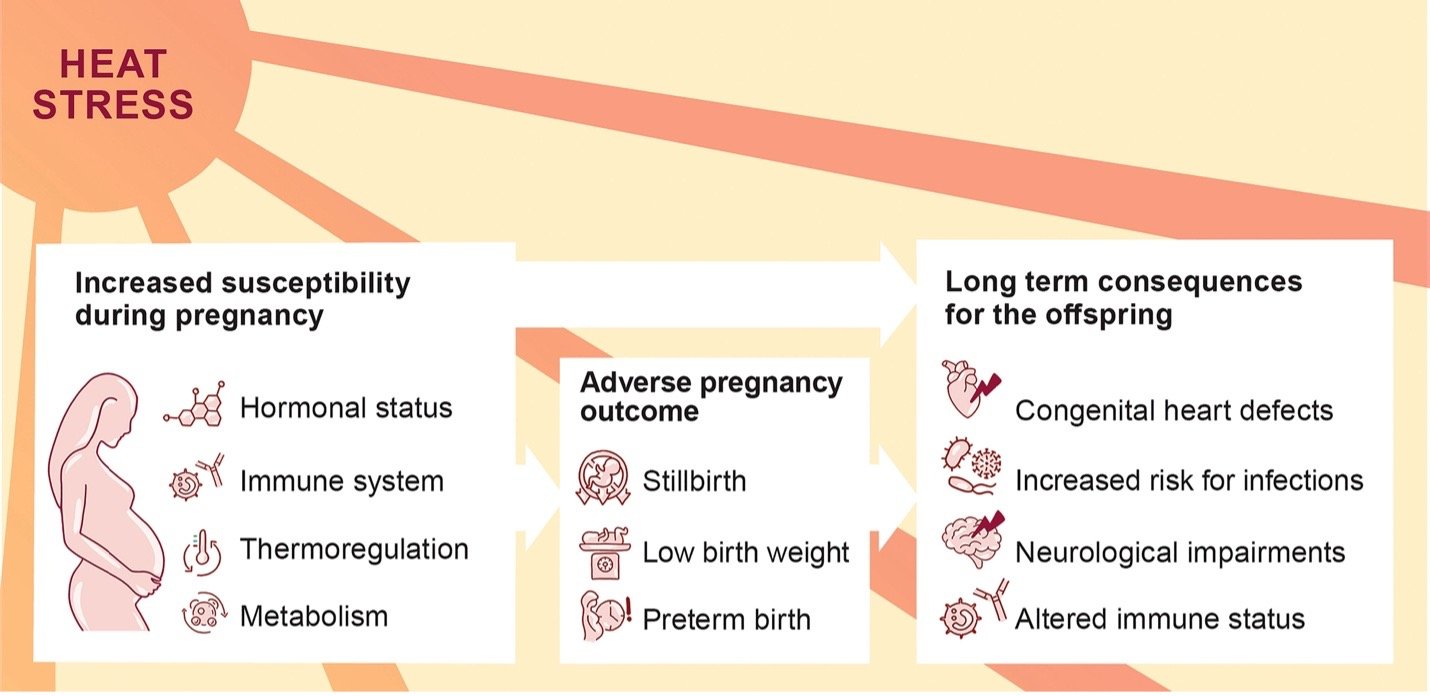

Increased susceptibility of pregnant women to heat stress with possible consequences for the progression of pregnancy and offspring’s health.

In 2023, the U.S. got slammed by 28 extreme weather events, including a massive heatwave that scorched the South and Midwest for months, taking 247 lives along the way (Smith, 2024). To add to that, it was also the hottest year on record since 1850 (Dahlman & Lindsey, 2024). Rising temperatures aren’t just making summers unbearable; they’re also affecting things we don’t usually think about, like fetal development. Climate change is showing up in some unexpected—and unsettling—ways, including altering how babies grow in the womb. Studies are now linking extreme weather and pollution exposure during pregnancy to a range of developmental issues, including delays, anxiety, ADHD, and even depression later in life (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023).

Our Changing Climate

Over the last 174 years, Earth’s temperature has been creeping up, with an average increase of 0.11°F per decade. That adds up to a total rise of 2°F since 1850 (Dahlman & Lindsey, 2024). While 2°F might not sound like much, it takes a massive amount of heat to push the global temperature even that little bit. And here’s where it gets real: the ten hottest years on record? They all happened between 2014 and 2023 (Dahlman & Lindsey, 2024).

This rising heat isn’t just uncomfortable—it’s dangerous. Even a slight bump in extreme heat days can increase health risks, especially for vulnerable groups. Cities across the U.S. are experiencing heat waves that last about four days on average, with the “heat season” stretching 45 days longer than it did in the 1960s (EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2024). With these heat-packed days stacking up, the risks for expectant moms and their babies are on the rise. More extreme weather means more prenatal impacts in the years to come.

Fetal Health and Climate Change

Developing babies are incredibly vulnerable to environmental stress, and climate change is only making things worse (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023). Research shows that when pregnant women experience extreme weather events, it can impact their babies in surprising ways. Studies have found that babies exposed to these stressors in the womb are more likely to have changes in temperament, lower activity levels, and reduced social engagement as infants. They may also face a higher risk of developing anxiety, depression, and even ADHD as they grow up (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023).

Around the world, studies link premature births, low birth weights, and stillbirths to extreme heat and air pollution—especially from fossil fuels and wildfire smoke (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023). And it doesn’t stop there: exposure to poor air quality, infectious diseases, and unsafe food or water can lead to birth defects, maternal health complications, and, in severe cases, fetal death (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023). The fetal nervous system, which is developing at breakneck speed, is especially sensitive to these kinds of damage. Prematurity and low birth weight, in turn, increase the risk for serious neurological issues like cerebral palsy, brain bleeding, and even vision problems (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023).

Although we’re still piecing together the full picture of how climate change affects fetal development, it’s clear that some stages of pregnancy are especially vulnerable. Identifying those high-risk times and populations is crucial for protecting the next generation (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023).

What Can We Do?

There’s no question we need big changes to tackle climate change’s impact on health, especially for pregnant women and children. On a global scale, that means slashing greenhouse gas emissions by shifting to clean energy, eco-friendly transportation, and more sustainable food production (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023). And we’re not just talking about climate benefits—these steps could help reduce health risks, too.

On a national level, policies need to adapt to make communities stronger against extreme weather. It’s about safeguarding children’s health by ensuring programs are in place to identify developmental delays early, provide disability assistance, and offer accessible mental health resources for kids (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023). Prenatal care should also be adjusted to give special attention to pregnant women exposed to extreme conditions (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023).

Locally, joining forces with climate action groups or reaching out to state representatives can make a big impact. Real change often starts close to home (American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica, 2023).

As climate change continues to intensify, its effects on the mental and physical health of kids are only going to grow. It’s alarming, yes—but with a solid strategy, from education and advocacy to policy change, we can protect future generations. Every effort counts when it comes to securing a healthier future for our children.

References:

American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica. (2023). Mental health and our changing climate: Children and youth report 2023. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2023/10/mental-health-youth-report-2023.pdf

Dahlman, L., & Lindsey, R. (2024, January 18). Climate change: Global temperature. NOAA. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-temperature

EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2024, June). Climate Change Indicators: Heat Waves. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-heat-waves#:~:text=Their%20frequency%20has%20increased%20steadily,been%20about%20four%20days%20long.

Smith, A.B. (2024, January 8). 2023: A historic year of U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters. NOAA. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2023-historic-year-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters

Image retrieved from: Arck, P.C., Diemert, A., Graf, I., & Yuzen, D. (2023). Climate change and pregnancy complications: From hormones to the immune response. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.114928